The following excerpt is authored by Lincoln Mondy, AFF’s Program Officer, and focuses on a recent staff and board learning trip to the Equal Justice Initiative’s Legacy Sites in Montgomery, Alabama. To read the reflection in its original unedited form, access Lincoln’s newsletter: The Creative Abolitionist.

***

Instead of focusing on the atrocities of enslavement and racial terror as artifacts of the past, the museum and connected sites frame these practices as the foundation for our current realities. Visitors are not left to mindlessly digest trauma. They are empowered to see how it’s all interconnected, guided by the dehumanizing myths of racial difference that have seeded the ground for white supremacy to endure. This is not by accident if you’re aware of the Equal Justice Initiative’s long, active, and vital role in challenging prisons and punishment in this country. Since 1989, EJI has represented people who have been illegally convicted, unfairly sentenced, or abused in state jails and prisons. Walking through the exhibit, it’s hard not to feel the same sense of urgency, care, and commitment that is surely required by their staff lawyers in order to work in the bowels of our punishment system — death row.

As you move through time, words and connections are clear. Precise language is offered to unlock individual aha moments. Language is also used to clear up popular narratives that have a deep-seated hold on our collective consciousness. For instance, when you hear the words “the Great Migration,” you may, like myself, have mental images of jazz, artistry, and bravery. Black people moving to the big city for new opportunities, making a way out of no way. Sure, but the truth-telling facts inside the museum challenge you to reconsider the migration for what it was: refugees fleeing racial terror.

EJI rightfully understands that you can educate a person all day long, but if you don’t provide accurate language that can break through propaganda, intentional silos, and vague platitudes, it’s a fool’s errand. Space is given to challenge commonly-held shared language so that even if a person’s entire life isn’t transformed by the experience, at least the intent of the learning can leave through words.

The museum is almost in a 1on1 conversation with you, cataloging all the historical events you should reconsider and reflect on.

- It may be known as the Transatlantic Slave Trade, but it was, more accurately, the global human trafficking of 13 million people.

- Reconstruction? Oh yeah, the 12-year period following the Civil War where a well-funded and power-gripping white upper class worked overtime to enshrine white supremacy into law.

- Yes, the 13th Amendment was passed in 1865 and does outlaw slavery, but the organized and well-funded white resistance allowed it to flourish for another century. Oh, and the 13th Amendments’ exception to slavery and involuntary servitude: prison labor.

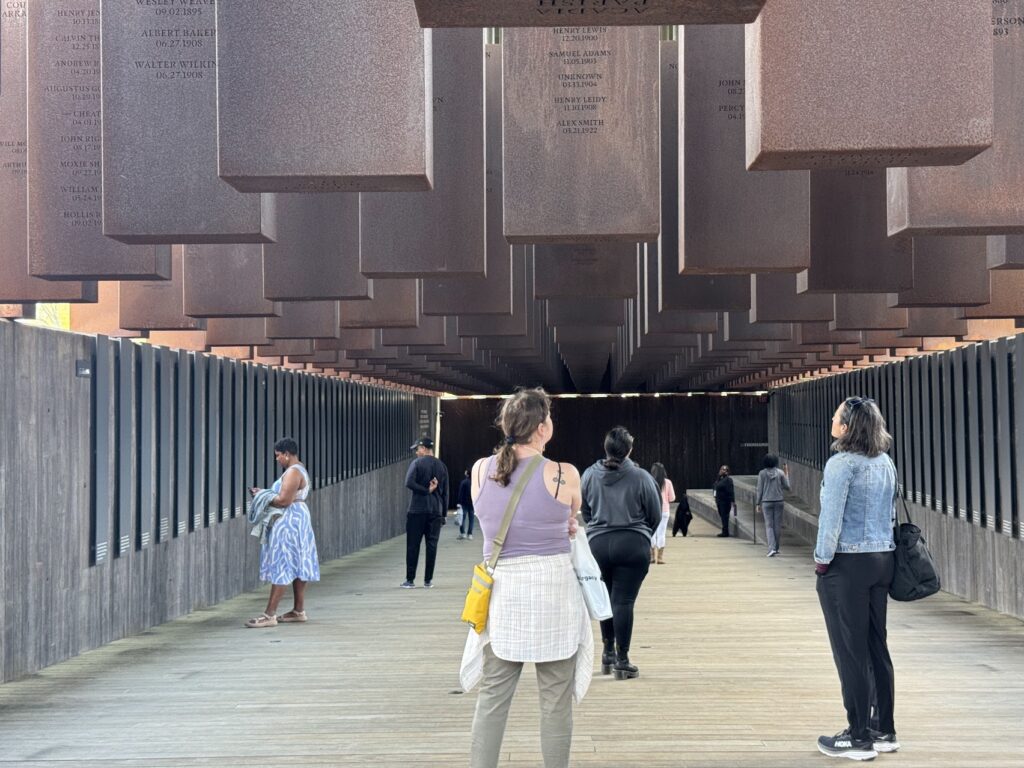

The narrative throughout the experiences of enslavement, racial terror lynching, segregation, and mass incarceration is clear and consistent. The design is both Brutalist and organic at the same time. There aren’t sharp corners in the exhibition that curtail off sections — there is only one path in and one path out. You begin in a dark room, underwater, with waves crashing over you via visceral audio, visual, and lighting design. You’re reminded that in addition to the 13 million Africans who survived their kidnapping by boat, nearly 2 million souls died horrific deaths in vast, dark seas along the way. While the design asks you not to look away, the wide halls and variety of learning materials around the room (e.g.,video, film, holograms, text) offer reprieve when you need it.

As you navigate the space, you unexpectedly go from rooms with supersized “auction pamphlets” filled with advertisements from slave owners describing the bodies and behavior of their state-designated property to a theater asking you to honor Mamie Till’s wishes and not look away at how racial terror and white supremacy disfigured her son, Emmett. Then you’re guided all the way up to mass incarceration. Unfortunately, it doesn’t feel like a leap at all. After the mass incarceration era, the path leads to a majestic, copper-ceiling room asking you to pause and reflect. The last room is a colorful art gallery right before a bustling museum lobby — another intentional design choice focused on acknowledging and honoring the horror you confronted.